[Note: This essay contains spoilers. My original September 12, 2012 review of The Master for Look / Listen can be found here.]

Last month The New Inquiry published an incisive essay titled “American Saints,” the subject of which is, in author Rohit Chopra’s phrasing, “the fetishization of the entrepreneur” in American cultural and political life. Overall, the piece is a trenchant slice of social criticism, but it is this early paragraph in Chopra’s essay, highlighted by Andrew Sullivan, that zeroes in on a phenomenon that has long needed a name:

The obsession with the figure of the entrepreneur reflects what may be called the “evangelical imagination,” in American society. I use the term broadly to refer to a style of thinking in which the act of adopting a set of beliefs and attitudes is seen as profoundly transforming both the individual and the state of the world. The term also invokes the missionary fervor with which the advocates of particular ideas, beliefs, or products seek to persuade others about the value of these notions or objects…

Chopra employs this idea of the evangelical imagination as an explanatory framework for what he perceives as the culture’s monomaniacal lionization of “Homo entrepeneuricus”. However, the concept is a useful one for understanding a distinctly American approach to all manner of ideologies, whether they are economic, political, religious, or philosophical. The evangelical imagination has a particular relevance for cinephiles at the present moment, as the phenomenon is one of the foremost thematic preoccupations of writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson’s brilliant, divisive new feature, The Master.

Moreso than any other American feature released in 2012, Anderson’s film has provoked a bumper crop of deep-focus critical assessments. In the past three months or so, a staggering number of words have been generated in an attempt to suss out The Master’s plot, themes, style, and various perceived strengths or weaknesses as an art object. Thus far, however, there has been little discussion of the prominent place of ideology in the film’s dense thematic landscape. In particular, The Master’s acidic criticism of the American zeal for a transformative, receivable Truth is one of its most enthralling aspects, and one that deserves serious attention.

***

One could hardly imagine an individual in greater need of a transformation (any kind of transformation) than World War II Navy veteran Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), who exhibits a host of compulsive, destructive behaviors. Freddie is a raging alcoholic with a predilection (and apparent talent) for concocting eye-opening elixirs from ingredients ranging from Cutty Sark to paint thinner. He will, however, swig straight Lysol in a pinch. His addiction routinely results in all manner of first- and second-order troubles. The booze keeps him snoozing through a dinner date with a lovely department store model, Martha (Amy Ferguson). It goads him into a pointless, adolescent scrap with a customer (W. Earl Brown) at the photography studio where he works for a time. Eventually, it finds him sprinting across a fallow field in California’s Central Valley, chased by Filipino cabbage-pickers who believe that Freddie’s homemade hooch has poisoned a fellow worker (Frank Bettag).

Boozing is just the most prominent of Freddie’s innumerable bad habits, however. He is routinely seized by a sexual mania that overwhelms his senses, not to mention his already-marginal social graces. During the War, when his fellow sailors construct a sand sculpture of an anatomically correct woman on a South Pacific beach, Freddie doesn’t just hump the effigy for a few seconds to elicit a laugh. He proceeds to finger the sand-woman’s vagina in detached silence, while the appreciative smiles of the gathered sailors gradually slacken in discomfort. (Phoenix adds a superlative physical flourish to this scene by offhandedly shaking the grit from his hand.)

Within every inkblot presented to him by a Navy psychologist, Freddie detects a pussy or cock or some combination of the two. Even his more poetic romantic outbursts are streaked with sexual frenzy. About to depart for China on a sea freighter, he whispers a dawn goodbye at the bedroom window of Doris (Madisen Beaty), the sixteen-year-old object of his desire, and then abruptly rips through the wire screen to embrace her. (The moment evokes William Hurt’s lust-crazed glass-shattering in Body Heat, albeit without the subsequent sexual release.) Freddie’s characteristic stance—crooked back, sunken chest, arms akimbo, hands resting on his bony hips—highlights his satyriasis. He seems to be ready to direct an animal thrust at anything that crosses his path, or perhaps straining (unsuccessfully) to keep his urges leashed.

Freddie’s gargantuan impulse-control problems appear to have been exacerbated by his wartime experiences. These are ambiguous, although sufficiently scarring that he is committed for a time to the care of Navy hospital for what was is euphemistically referred to as his “nervous condition.” Later in the film, he confesses to having slain an unspecified number of “Japs” during the War, and although he claims that he feels no guilt for these murders, it’s plain that he is suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. However, shell shock (as it was then called) is not the only explanation for his erratic, violent tendencies, which the film traces back (in part) to a family history of alcoholism, mental illness, and emotional and sexual abuse.

Like all addicts, Freddie is in deep denial about the extent to which his actions are problematic, preferring to project the persona of a hard-working, easy-going fellow with no particular troubles. Questioned by a Navy doctor, he exhibits little remorse for past “incidents,” such as a drunken attack on an officer or a sobbing breakdown provoked by a letter from Doris. Freddie’s reaction when confronted with any accusation is to first refute and then minimize. “There’s no problem” is his mantra, but anyone with eyes can see that there most definitely is a problem.

It’s clear that Freddie desperately needs to change his ways or he will soon meet a violent, booze-soaked end, but it’s less obvious how such a change might come about. For some individuals, the day-to-day structure provided by military life serves as a much-needed organizing principle that nurtures self-discipline, but Freddie is not that sort of individual. Even threats of imprisonment or hospitalization have evidently done little to curb his drinking, libido, or rage. He’s as untamable as a mad rattlesnake, prone to lash out at anything that grazes him.

Freddie’s dissolute behavior positions him as the potential hero in a classic Conversion Story, in which a lost soul is transformed by exposure to a Truth (usually religious in nature). In such tales, the convert is snatched from the talons of self-destruction and blessed with a new sense of completeness and purpose. However, while The Master relies in part on the conventions of the Conversion Story, the film is eventually revealed as a bloody-minded refutation of the very notion of conversion. Far from offering a boilerplate portrait of Augustinian repentance and zeal, The Master depicts Freddie’s attempt to reform himself through ideological devotion as a futile and even catastrophic endeavor.

***

Bottoming out for the umpteenth time, Freddie stows away aboard the Alethiea, a luxury ship moored in San Francisco Bay. Upon awakening blearily the next morning, he is led into the stateroom of "The Master." This is Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a self-described "writer, doctor, nuclear physicist, and theoretical philosopher," who also presents himself as the commander of the vessel. During their first conversation, Dodd observes that Freddie is a “hopelessly inquisitive man.” This phrase does not seem to describe the volatile drunk and sexual obsessive that the film has thus far depicted. However, the longing for answers to questions (and for solutions to dilemmas) proves to be one of the fundamental forces that propels Freddie’s Conversion Story—and ultimately derails it utterly.

From the moment of their initial encounter, the complex relationship between Freddie and Dodd becomes the dramatic centerpiece of the film. Freddie’s stance towards Dodd’s pseudo-religious self-help movement, the Cause, is informed to a large extent by his stance towards the Master. This is unsurprising, given Dodd’s status as the Cause’s first and only prophet. However, Dodd also develops an affinity for Freddie that goes beyond the normal dynamic of a high priest and his acolyte, with Dodd exhibiting behavior that is faintly paternal, fraternal, and homoerotic. Both men are eventually disillusioned by the failures of the other, and those failures become a part of the film’s broader criticism of ideology gone haywire, and of the evangelical imagination’s stark limitations.

To the skeptical eye, Dodd’s Cause appears to be a mish-mash of past-life regression, positive-thinking gobbledegook, and laughable snake oil claims. In its outlines, the Cause bears some similarities to L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics movement and its religious descendant, the Church of Scientology. Likewise, Dodd’s biographical details and personality traits partly resemble those of the historical Hubbard. The dramatic heft of The Master relies to some extent on the evocative power of such similarities, permitting the film to exploit the prominent position of Scientology within the American religious, economic, and cultural landscape. (Undeniably, Scientology is a profoundly American faith in both its origins and character, with its pay-to-play system of spiritual advancement and institutional reverence for celebrity and financial success.)

However, the fictional nature of the Cause is essential to The Master’s success as a bleak rebuttal of the zealous advocacy that characterizes the evangelical imagination. Anderson’s centering of the film’s events on an invented cult shifts the focus away from the creeds or rituals of any particular real-world faith. This enables the film to preempt accusations of sectarian motive and circumvert slogs through digressive theological mires. Instead, The Master takes as its theme the phenomenon of ideology, and in particular the ways in which ideological systems are intrinsically incapable of confronting and addressing their own failures. In revealing the weaknesses of a non-existent religious movement, the film thereby confronts all the -isms that promise a sweeping transformation of the self and society.

This sort of transformative power is strongly associated with American evangelical Christianity; hence Chopra’s appropriation of the movement’s terminology for his essay. For Americans who were raised in the evangelical subculture, the holistic character of Biblical truth—its alleged applicability to every aspect of life and every problem one could potentially confront—is a familiar concept. One’s Christian faith, and specifically a non-literal “literal” reading of the Bible, provides a yardstick by which all judgements can be assessed for righteousness, from the most banal consumerist choices to legal interpretations of the United States Constitution.

To those Americans who stand outside the evangelical Christian bubble, the all-encompassing reach of its worldview can be difficult to fully comprehend and appreciate. Occasionally, the flitting sunlight of YouTube will illuminate a prominent true believer who takes the evangelical imagination to its logical endpoint: cultural hegemony enforced at the point of a sword (or at least a bureaucrat’s pen). Such a moment was recently highlighted when video emerged of Representative Paul Broun (R-GA) extolling the Bible before a like-minded audience:

What I’ve come to learn is that it’s the manufacturer’s handbook, is what I call it... It teaches us how to run our lives individually, how to run our families, how to run our churches. But it teaches us how to run all of public policy and everything in society. And that’s the reason as your congressman I hold the holy Bible as being the major directions to me of how I vote in Washington, D.C., and I’ll continue to do that.

As Broun’s words illustrate, the evangelical imagination approaches Christianity not merely as a set of principles for confronting day-to-day ethical dilemmas, or as a source of personal fortitude in the face of adversity. The church is, rather, a cultural force that can and must be implemented in every facet of human life. Such hubris is hardly the exclusive domain of Christianity, nor is it limited to religious movements. It is the common thread of every ideological system when it imagines itself at the End of History and subsequently becomes infected with sweeping self-importance.

Just as all ills—whether personal or social—are rooted in the absence of the ideology, there are no problems that can stand before the ideology’s gleaming truths. This stripe of grandiose, magical thinking creates space for truly ludicrous claims. In The Master, Lancaster Dodd insists that the Cause’s “de-hypnosis” methods can achieve aims as grand as establishing world peace and curing leukemia. (“Some kinds of leukemia,” Dodd helpfully clarifies.) Such statements directly evoke Scientology’s claims that its pseudo-scientific hoodoo can heal all manner of psychiatric ailments. However, one is also reminded of the remarkable assertion of George W. Bush’s neo-colonial Iraq administrator L. Paul Bremer that right-wing laissez-faire economic policies were the cure-all for the post-Saddam, U.S.-instigated chaos in that country. How exactly a flat tax rate would have blocked the bullets that killed tens of thousands of Iraqi civilians is a mystery on par with how Dodd’s interrogation exercises can abolish cancer.

***

Were The Master especially concerned with highlighting the silliness of the Cause’s self-help claims and quasi-mystical newspeak, then one might justly accuse Anderson of fashioning a ideological scarecrow to pummel into submission. However, while the film presents the Cause’s beliefs as almost laughably wobbly at times, Dodd is hardly portrayed as a failure. He has, after all, amassed a nationwide assemblage of followers, many of whom sincerely believe that his methods have helped them overcome physical and psychological challenges. The Master is, if nothing else, a consummate pitchman and manipulator, capable of convincing his devotees that his Victorian parlor tricks are providing dramatic results in their daily lives.

The vacuousness of the Cause plays a vital narrative role in The Master, but the film’s dramatic focus rests on characters’ reactions and counter-reactions to that vacuousness. This is crucial to the film’s grace and sophistication: its criticism of the evangelical imagination is discreetly expressed through the experiences of its characters. Specifically, the film employs the person of Freddie Quell to illustrate the paradox of a zealot who does not see the divine light that fellow believers claim to sense. Fundamentally, The Master is the story of how Freddie responds when confronted with this alienating situation, and how Dodd in turn responds to the presence of a stillborn apostle in his flock.

Approaching The Master in this way permits a strikingly clear division of the film’s scenes into chapters, with significant shifts in Freddie’s relationship to the Cause serving as narrative breakpoints. The scenes that precede Freddie’s first encounter with Dodd aboard the Aletheia function as a prelude, establishing significant facts about the former man’s character and past (although some revelations are held in reserve for later). In the chapters that follow, the film creates a sense of expectation through the promise that Freddie will experience a “profound transformation,” in Chopra’s phrasing. This epiphany never arrives, resulting in a story that is characterized by repeated episodes of aimlessness and fizzled potentiality. The viewer, like Freddie, expects that the burning bush will eventually speak, but The Master is utterly ruthless in its silence.

The film’s setting encompasses a sequence of localities that are not revisited (save in flashback), conveying the sensation of trudging towards an ever-lengthening horizon. The action drifts to San Francisco, New York, Philadelphia, Arizona, Massachusetts, and England, as though a moment of clarity lies just over the next hill. (The South Pacific of Freddie’s war memories, meanwhile, seems to exist outside of time, bookending the film with its churning turquoise waters and sandy mother-lover.) The rootlessness of setting is an outgrowth of Lancaster Dodd’s itinerant nature. Recalling Christ, he is a holy man without a temple, dependent on the largesse of well-heeled, more sedentary benefactors in order to sustain himself and preach his gospel. Of course, in contrast to Christ’s asceticism, Dodd appreciates the finer things in life, and has no compunctions about borrowing a wealthy follower’s stately pleasure ship for his daughter Elizabeth’s (Ambyr Childers) maritime wedding.

I. Aboard the Aletheia

Having discovered that he is the guest of an enigmatic self-help author who answers only to the title “Master,” Freddie is understandably guarded. Even when confronted with Dodd’s disarming observations regarding his alcoholism and anger—apparently gleaned from a single off-screen night of misbehavior—Freddie repeats his Navy hospital tactics and simply denies that he has any problems. The wedding of Elizabeth and Clark (Rami Malek) and the following days at sea expose Freddie to the Cause’s strange jargon and rituals, albeit offhandedly at first. During the wedding reception, Dodd’s son Val (Jesse Piemons) asks Freddie whether he has performed any “time-hole work,” a question to which the latter man responds with his characteristic grinning uncertainty. Playing along and telling people what he suspects they want to hear proves to be a favored strategy for Freddie when he is on unfamiliar ground.

Freddie is generally captivated by Dodd’s self-assured charisma, and pleased by the man’s appreciation for his mixology talents. (Dodd, who is a guilt-wracked sensualist at heart and loves mystifying the mundane, coyly refers to Freddie’s alcoholic concoctions as “potions”.) Where the Cause’s bizarre beliefs and practices are concerned, however, Freddie exhibits a blend of mild curiosity and eye-rolling disbelief. During a strange group session, Dodd’s wife Peggy (Amy Adams) explains in hushed tones that the Cause’s methods allow subjects to revisit formative in utero experiences, and even regress through countless past lives. “We record everything,” she declares, hands on her pregnancy-swollen stomach, and although Freddie nods in agreement, he doesn’t seem to know what to make of this statement. Spiritual matters don’t hold much attraction for him. Confronted with a bank of headphones that pump a recording of a droning, anti-carnal diatribe read by Dodd, Freddie defiantly scribbles a crude proposition to the woman sitting across from him.

Perhaps sensing Freddie’s growing frustration, Dodd asks him to participate in the Cause’s signature sacrament, a marathon of repetitive, confounding, and deeply personal questions referred to as Processing. Freddie’s Processing is one of the film’s pivotal scenes: Dodd succeeds in cracking open the man’s shell of stiff-lipped denial, and exposes the core of raw pain underneath. The ease with which the Master does this, and Freddie’s eagerness to please him by “succeeding” at the Processing, convince the latter man not only of Dodd’s wisdom, but of the ideological merits of the Cause. The silliness of past lives and time-holes aside, Freddie is unable to deny that Dodd has access to some secret way of seeing the world, enabling him to quickly discern a subject’s most private shames.

To a skeptical observer, standing outside the emotionally heightened Processing experience, Dodd’s methods seem mundane, comparable to the cold readings performed by strip-mall psychics and cable-show mediums. His questions are so generalized as to be pointless: Do your past failures bother you? Do you care how others see you? Is your life a struggle? Is your behavior erratic? Dodd creates false familiarity with such inquiries, priming Freddie to answer other, more specific questions with unthinking frankness. Furthermore, by asking the same questions repeatedly and staging the entire Processing as a kind of endurance test, the Master creates a sense of disorientation that invites non-rational responses. Freddie becomes wholly caught up in the Processing, going so far as to strike himself violently as punishment for repeatedly “failing” the rite.

The tone of Freddie’s Processing scene is ferociously intimate, one part confession and one part psychoanalysis. It also possesses a strikingly erotic undertone. After excavating all of Freddie’s secrets and declaring him “the bravest boy I’ve ever met,” Dodd shares a cigarette and a turpentine cocktail with his new devotee. (Dodd’s moaning exultation after a swallow of Freddie’s potion is nakedly orgasmic, and will be echoed later in the sounds Peggy’s bathroom sink handjob elicits from her husband.) However, the sexual dimension to Freddie’s Processing ultimately proves compelling not so much for its intimations about the Dodd-Freddie relationship as for its reflection of the Cause’s supposedly transformative qualities. Like the virgin freshly awakened to the secret world of sexuality, Freddie sees his surroundings through new eyes. (There will, of course, be eventual disappointments when the lover’s blemishes and aggravating habits become more evident with time.) He has witnessed the light on the road to Damascus, and has submitted himself to the ideal of the evangelical imagination: The Truth having (allegedly) enacted a profound change on him, he is compelled to venture into the world to participate in the dispersal of the Good News.

II. New York City

For Freddie, however, the afterglow of his Processing—and any attendant positive effects on his self-destructive behavior—is short-lived. He willingly accompanies the Master and his entourage to New York City, where Dodd is received like an honored guest by an elderly, well-to-do patron, Mrs. Drummond (Patty McCormack). It is almost immediately apparent that Freddie’s ways have not been mended by the dubious miracle of Processing. Introduced to Mrs. Drummond, he gauchely fingers the dowager’s necklace, sizing its value with reptilian listlessness. Thereafter he slips away to a nearby room to swipe knick-knacks. The rationale for this kleptomania is not apparent, but is consistent with Freddie’s impulsive, anti-social pre-Processing behavior. Likewise, the Cause has evidently not deprived Freddie of his taste for alcohol, as he orders a scotch from the bartender. Later, perhaps after imbibing a few more fingers of whiskey, Freddie laughingly hurls food at John More (Christopher Evan Welch), a writer who dares to question Dodd’s methods.

Freddie’s failure to be dramatically remade by Processing and his rapid regression to negative thoughts and actions are stark expressions of a pattern that will be repeated throughout the film. Presented with a wooly promise of personal transformation, Freddie submits himself to the Cause’s ministrations, only to quickly slip back into his characteristic ugly behaviors. While he now directs a measure of his aggression outward at the perceived enemies of the Cause (such as More), that aggression has not subsided in the least. New Freddie does not embody a tamed animal, but a mere redirection of snapping jaws towards heathen “attackers,” in Peggy’s self-righteous phrasing. Eventually, Freddie takes the initiative to counter-attack in the name of the Cause: calling upon More during the wee hours, he forces his way into the skeptic’s apartment under false pretenses and subjects the man to an apparently brutal beating.

As will be illustrated later in the film, Freddie is a poor proselytizer, as he lacks the person-to-person charisma and unflappable demeanor that such a task demands. In addition to lacking the profound transformation of the evangelical imagination, he is comically ill-suited for the missionary aspects of such thinking. His hair-trigger temper and rattling furies, however, make him an effective religious enforcer, a junkyard dog who can be unleashed for the purposes of a kind of inverted advocacy. While rank-and-file members of the Cause woo lambs into the fold, Freddie prefers to prowl the perimeter in search of wolves (and wolves in sheep’s clothing). Freddie’s assumption of the legbreaker-in-chief role is startling, in part because of its rapidity, but also because it contrasts with the apparent disingenuousness of his conversion. One generally expects inquisitors and conquistadors to be true believers, not secret apostates.

Dodd, for his part, makes a grand show of scolding Freddie for the assault on More, and of emphatically declaring his follower’s actions to be subhuman. However, the sincerity of Dodd’s outrage is questionable. His disapproving scowl quickly melts into a grin, and he warmly repeats an earlier claim of deja vu, a suspicion that he and Freddie have met somewhere before. Dodd’s disapproval at Freddie’s bad acts is rendered toothless by his reassertion of intimate familiarity. This creates confusion for Freddie, a confusion that will only be compounded by subsequent dissonances in Dodd’s responses to his behavior. For now, it is sufficient to observe that the teacher’s reaction to moral stumbles pantomimes disapproval while drawing the convert closer. This two-step will become more difficult to achieve as Freddie becomes more agitated at the Cause’s shortcomings.

III. Philadelphia 1 - Freddie Stumbles

The Master and his entourage soon depart for Philadelphia, where they are are welcomed by another devoted follower and benefactor, Helen Sullivan (Laura Dern). In contrast to Mrs.O’Brien’s ritzy Gotham apartment, Helen’s home is a picture of tree-lined middle-class coziness, and proves to be far more accommodating to long-term occupancy by the Cause faithful. Freddie's uncertainty about the movement at this point in the story is highlighted by a surreptitious thigh-grope from Elizabeth. (The inconsistencies are accumulating: Is lust to be discouraged or not?) Later, Freddie watches drowsily from a corner as Dodd heartily belts out a bawdy song to the delight of assembled Cause aspirants. From Freddie’s alcohol-soaked viewpoint, the women in the room suddenly appear to be unclothed: laughing, applauding, and shameless in their nakedness. Peggy Dodd, partly concealed by her armchair, turns to glare at Freddie with what resembles mingled pity and fearfulness. She seems to sense the latent mischief that bubbles as Freddie’s lazy, licentious eye wanders over the revelries.

Theat night, after aggressively asserting her power over Dodd with the aforementioned bathroom sink sex act, Peggy awakens a slumbering Freddie to demand that he stop his boozing ways for good. Still half-asleep and three-quarters-drunk, he thickly assents to this request, but by the next day he can already be observed nipping from a flask. Not coincidentally, it is this moment that Freddie chooses to reprimand and threaten Val for his faithlessness. “He’s making all of this up as he goes along,” the visibly bored Val observes regarding his father, “You don’t see that?” Of course, Freddie has harbored suspicions regarding Lancaster Dodd’s charlatan character from his first encounter with the man, but the convert’s craving for pragmatic solutions to his woes has thus far been trumped by his desire to belong. For Freddie, this latter need is expressed by the fulfilment of his enforcer duties. Rather than confront the hollowness of Dodd’s teachings (or his own failure to self-improve), Freddie retrenches his devotion by policing his fellow converts for thought-crimes.

Unfortunately for Freddie, this is also the moment when Philadelphia’s Finest appear to arrest Dodd for his larcenous schemes. Emboldened by his own guilt, Freddie leaps to Dodd’s defense with bestial fury. He becomes uncontrollable, flailing and squirming like a feral animal while he is handcuffed and hauled away. Later, Master and student are placed in adjoining jail cells, and the partitioned space (captured in the same shot) sharply contrasts the two men. Dodd slouches passively, regarding Freddie with disgust as the younger man engages in a frothing, self-destructive frenzy: slamming his hunched back into the hanging cot, writhing out of his shredded shirt, kicking the toilet into a porcelain ruin. (The latter echoes’ Phoenix’s destruction of a bathroom sink as a drug-crazed Johnny Cash in Walk the Line.) “Nobody likes you but me,” Dodd observes sneeringly. He also asserts that Freddie has not yet defeated the supposed eons-old spiritual ailment that is the cause of his alcoholism and violent rage. The profound transformation promised by the Cause is not yet complete.

Dodd’s jailhouse admonishments to Freddie provide a striking illustration of the ways in which the purveyors of the evangelical imagination address moments of crisis in believers' lives. Dodd chastises Freddie for his aberrant behavior, painting a picture in which Freddie’s self-destruction is fueled by external (and extra-temporal) forces, but can also be attributed to his own lack of will. Dodd’s remedy for Freddie’s recidivism is vague: He must, apparently, redouble his efforts, get serious about reforming his ways, and really try this time. There are no specific prescriptions other than a need to affirm the ideology’s Truth and submit to it more completely. (That the Cause’ exact doctrines are hazy, at best, serves to underline that the film’s criticisms are directed at the phenomenon of creeds rather at than their specific content.)

The focus on an individual believer’s failure of will—as opposed to the failures of the ideology itself—is a recurring preoccupation of the evangelical imagination. It is not, needless to say, limited to religious movements. Political blogger Matt Yglesias famously articulated the “Green Lantern Theory of Geopolitics” in reference to the neoconservative obsession with “will” and “resolve” in American foreign policy:

...[The Green Lantern ring] lets its bearer generate streams of green energy that can take on all kinds of shapes. The important point is that... what the ring can do is limited only by the stipulation that it create green stuff and by the user's combination of will and imagination. Consequently, the main criterion for becoming a Green Lantern is that you need to be a person capable of "overcoming fear" which allows you to unleash the ring's full capacities.

Suffice it to say that I think all this makes an okay premise for a comic book. But a lot of people seem to think that American military might is like one of these power rings. They seem to think that, roughly speaking, we can accomplish absolutely anything in the world through the application of sufficient military force. The only thing limiting us is a lack of willpower...

What's more, this theory can't be empirically demonstrated to be wrong. Things that you or I might take as demonstrating the limited utility of military power to accomplish certain kinds of things are, instead, taken as evidence of lack of will.

This succinctly describes the conundrum facing Dodd and all those who champion a universally applicable ideological framework. The Cause can never be wrong, so any obvious failures that it appears to birth—for example, a man who has been Processed by the Master himself, and yet continues his thieving, boozing, lecherous ways—must be the result of a lack of individual resolve (or else a sinister plot). This remorseless logic is demonstrated in a scene that follows Freddie’s jailhouse fit, where Dodd, having presumably been freed on bail, dines with his family. Peggy, Elizabeth, and Clark all tentatively raise the subject of Freddie’s out-of-control behavior, suggesting that the man might be a nefarious agent dispatched to discredit the Cause, a venal thief seeking to swipe the Master’s unfinished manuscript for a tidy profit, or simply a madman who is beyond any kind of mental or spiritual salvation.

Dodd, in contrast to the bristling annoyance he displayed with Freddie in jail, hears these suspicions out with calm attentiveness. However, he responds by matter-of-factly asserting that Freddie is not unreachable, and that his bad acts are the result of the Cause leadership’s own ministerial deficiencies. The failure of will actually belongs to Dodd, and to every member of the Cause who has given up on Freddie. In this way, Dodd slyly reverses the characteristic criticism of the flaccid will in the evangelical imagination, appearing humbled by his own deficiencies rather than scolding towards his acolyte. However, as the film later demonstrates, even Dodd has his limits. A wayward follower must be reformed or expelled, lest their continued existence serve as a demonstration of the ideology’s inadequacies.

IV. Philadelphia 2 - Freddie Reborn

Freddie’s brief exile in the custody of the Philadelphia police is the only significant narrative breakpoint that does not correspond to a shift in geographic setting. When the wayward convert returns to Helen’s home, Dodd embraces the man warmly and laughingly, their hug devolving into an adolescent wrestling match on the lawn. This horseplay manages to tear the leg of Freddie’s trousers, with both echoes his earlier clothes-shredding frenzy and foreshadows the upheavals to come. (Despite the Prodigal Son kabuki that Freddie and Dodd play out, there has been no true repentance or rehabilitation.) The Master’s jocular paternalism serves to assert his authority and solidify his earlier dinner table statements. The matter is not up for discussion: Freddie will be permitted back into the fold.

Such forgiveness comes with conditions, however. Much of the remaining time that the film spends in Philadelphia is devoted to the Cause’s elaborate efforts to bring about Freddie’s tardy profound transformation. Dodd subjects his black sheep to a series of bizarre exercises supposedly intended to urge him “toward existence within a group, a society, a family.” As has been noted, Freddie’s desire for acceptance within a social group is one of the primary motivations that drives him towards Dodd and the Cause. However, mere tribal identification with the movement is not sufficient: the Cause demands that its devotees also exhibit behavior that validates its ideology of personal improvement. The drunk must walk a sober path, the satyr must become chaste, and the violent criminal must transform into a peaceable emissary. Freddie’s place within the Cause is threatened by his failure to achieve an epiphany, and Dodd is determined to bring one about by any means necessary.

Examining Dodd’s motivations with a cynical eye reveals the cunning in his strategy. Having attributed Freddie’s failings to the Cause’s lack of pastoral will, Dodd is now obligated to demonstrate significant effort in the mission to reform his follower. If Freddie backslides yet again after such a campaign, then his misbehavior can be justly blamed on his lack of will rather than Dodd’s. It does not bode well for Freddie, then, that the Master’s rituals (“applications,” he calls them) are perplexing and opaque. They seem to be designed not to spark enlightenment within Freddie, but to break his will. In other words, they resemble a kind of psychological torture. Underlining the point, the film repeatedly cuts between the exercises to which Freddie is subjected, jumbling time’s passage and mimicking his increasing disorientation as Dodd’s ministrations wear him down. It is ultimately unclear whether Freddie’s marathon rehabilitation takes place over the course of a few hours or several days.

In one application, Dodd has Freddie and Clark face one another while seated, and orders each man to exhibit “no response” to the other’s statements, no matter how agitating their words might be. Clark goes for the jugular: he repeats the name of Freddie’s lost adolescent love, Doris, revealing that Dodd has shared the most intimate revelations of Freddie’s first Processing with the other members of the Cause’s leadership. Freddie, when his turn comes, merely asserts himself through his veteran status and childishly expresses a desire to fart in Clark’s face, calling back to a joke he and Dodd once shared.

Freddie is also observed seated across from Peggy, although there his challenges are different. At one point she reads pornographic literature out loud to him. At another, she orders him to “make” her eye color change. (Will, once again, is claimed to be the means by which the believer achieves change.) Reflecting Freddie’s aspirational point-of-view, Peggy’s irise do in fact dissolve from bright blue to inky black on command, providing the subtlest of the film’s handful of magical realism flourishes.

In the most harrowing application, Dodd commands Freddie to walk back and forth, eyes closed, between a wall and window, touching each and describing the sensation. This exercise is at first conducted in front of an assembled throng of rapt Cause followers, but Freddie is also observed repeating his ping-pong path in solitude. To Freddie, the rite seems monumentally pointless at first, and his attitude appears to swing primarily between dull half-attention and violent irritation. In some shots, however, he seems to be lost in an ecstatic reverie, and his verbal renderings of wall and window take on a hallucinatory quality. (At one point, he describes the window as a Ferris Wheel.) The psychological effects of Freddie’s mental endurance tests have begun to reflect the collapse of time and space that the Cause asserts is the means to rectifying aberrant behavior. Yet when Dodd finally—and arbitrarily, it seems—declares “end of application,” Freddie’s response upon opening his eyes is incredulity. “You gotta be kidding me? That was it?” If Freddie has had a profound transformation, it is invisible to the viewer’s eyes.

Later, Peggy appears before the Cause devotees to deliver a beaming announcement: Dodd’s second book is at last ready for publication, and the movement will hold its first annual conference in Phoenix, Arizona to mark the momentous event. Unable to allow a metaphor to dawdle without a little shove, Peggy predicts that the Cause, like the flaming bird of myth, will be reborn following the setbacks experienced in New York and Philadelphia. The unmentioned phoenix in the room is, of course, Freddie, who should by all rights be enjoying a second, more enlightened life thanks to Dodd’s close attentions. However, the straying sheep, as usual, proves to be a problem that the Cause cannot solve, and Freddie’s ability to fake his way through that coveted “existence within a group” begins to crack.

V. Phoenix

With the Cause’s pilgrimage to Arizona, the relationship between Freddie and Dodd superficially appears to have been restored to its past levels of warm interdependence. Freddie serves as the photographer for the Master’s new publicity shots—posing him in kitschy Western surroundings—and their exchanges are full of joking camaraderie. However, the fissures in the apostle’s faith are becoming visible. Although Freddie exhibits childish enthusiasm (and talent) when recording a radio advertisement for the Cause’s conference, his ambivalence and frustration are palpable when he is tasked to hand out fliers to disinterested and hostile Phoenicians. Proselytization isn’t Freddie’s wheelhouse, and when confronted with such duties, he is reminded that his own reformation is incomplete, his epiphanies are fraudulent, and his bad habits crouch nearby like stalking predators.

In a scene bubbling with indefinite tension, Freddie accompanies a gun-toting Dodd on a enigmatic trek into a narrow desert canyon. The purpose of the quest is unclear at first: Is this some new, menacing application, or perhaps a purifying wilderness exile akin to those undertaken by Christ and John the Baptist? Eventually, Dodd and Freddie unearth a strongbox, which is revealed to contain the Master’s unpublished manuscript. Like the golden plates from which Joseph Smith supposedly transcribed the Book of Mormon, Dodd’s wisdom represents a kind of buried ideological treasure, waiting to be delivered to the world. The air is briefly electric with menace, as Dodd silently surveys the horizon for threats—an Apache war party or swarm of flying saucers seem equally likely. Clark’s earlier dinner table accusation floats in the air: Did Freddie actually ask about the monetary value of Dodd’s unpublished work? Does Dodd secretly believe that Freddie cannot be reformed? Are the guns loaded? Then the men suddenly set off back to civilization, the awful potential of the moment passing.

The doubts linger, however, and as the conference kicks off in a modest theater space—all linoleum and sad party streamers and tent revival piano tunes—both Freddie and Dodd betray a crumbling confidence. Dodd seems more anxious than usual, and his prefatory remarks on his second book, The Split Saber, have a slipshod, rambling quality has thus far been absent from the Master’s spiritual pontifications. When Helen asks about a single word change in the book's description of Processing, Dodd explodes, “WHAT DO YOU WANT?!” This moment of exasperated rage not only echoes the Master’s own profane outburst at More earlier in the film, but it also highlights the stress that Freddie’s very presence as an unrepentant, unreformed believer is placing on the Cause’s credibility.

Freddie, meanwhile, is outwardly calm but seething within. In one of the film’s singularly great shots, he paces slowly in a wide back room where copies of Dodd’s latest tome are piled on tables. Eyes closed, he lazily retraces his old route between the (now-imaginary) wall and window. Visiting New York disciple Bill William (Kevin J. O’Connor) wanders in from the right, and Freddie’s metronome path is smoothly diverted. He imposes himself between Bill and the hubbub in the front of the building. Signals abound that Freddie’s enforcer duties are about to boil over into violence, even before Bill injudiciously declares that The Split Saber “stinks”. Freddie passes a cart laden with bottled chemicals, recalling the link between his alcoholism and his temper. Bill limply carries a plate spattered with half-eaten red food that foreshadows bloodshed, and also clutches his hat, exposing his bald pate for a pummeling. When Freddie leads Bill around back and unleashes a savage beating on the man, it is unsettling but thoroughly unsurprising.

The assault on Bill proves to be the moment when the bitter reality of Freddie’s situation becomes apparent: he is completely incapable of reform, and therefore will inevitably be cast out of the Cause’s embrace, lest his presence embarrass the Master. Freddie seems to sense this fact clearly at last, as he collapses in defeat on a bench, sobbing into his hands. He will never achieve his profound transformation. Perhaps this is due to the severity of his spiritual wounds, which run too deep to ever be healed by any ideological palliative. Perhaps it is due to some incompatibility between the nature of his trauma and the Cause’s curative methods. Or perhaps it is merely because Dodd’s wisdom is a sham, and his techniques do not provide anything but a mumbo-jumbo-wrapped placebo. Ultimately, it does not matter. In his desperation to alleviate the pain of his life’s dread pattern, Freddie has hitched himself to an ideology that has proven inadequate for that purpose. The lords of that ideology will not suffer to have their deficiencies paraded before them in human form.

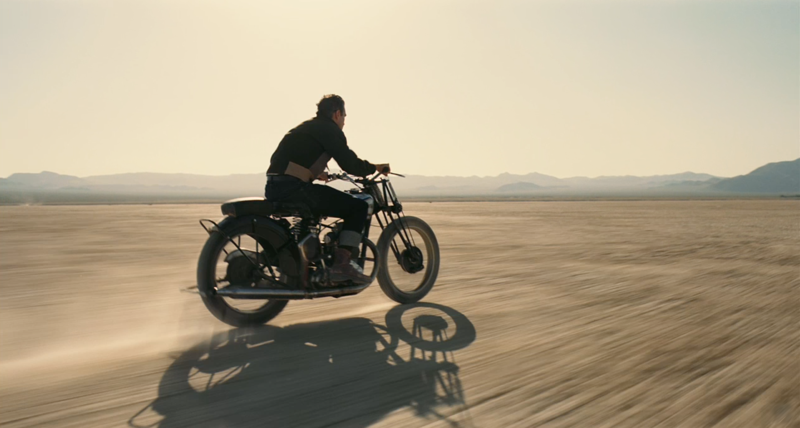

Dodd later accompanies Freddie out onto a gleaming desert plain for yet another outlandish, ad hoc exercise, with Elizabeth and Clark tagging along. The Master explains that the objective of “Pick a Point” is to ride a motorcycle a high speed in a rigorously straight line, and then demonstrates by rocketing across the wastes with boyish whoops of glee. When Dodd returns, dust-coated and grinning in satisfaction, the anticlimactic pointlessness of this latest ritual is depressingly apparent to both the viewer and Freddie, and only highlighted by Elizabeth’s vapid cheerleading (”Whoo! Go, Daddy!”). Dodd dismounts and offers the motorcycle to Freddie, who rides it in the opposite direction, diminishing to a wavering speck on the sun-baked horizon. “He’s going very fast,” Dodd observes with dry anxiousness. Then it is dusk, and Freddie has not returned, and it is clear that he is not going to.

Superficially, Freddie’s flight seems a childish response to the intractable spiritual position in which he finds himself. Bereft of the transformation that the Cause has promised, and unable to face the scrutiny of his fellow believers (or the disapproval of his Master ), he turns on his heel at an opportune moment and simply runs. Yet the abruptness of Freddie’s departure denies Dodd and the others the opportunity to subject him to further enticements and rituals. Given Freddie’s apparent susceptibility to the siren call of social acceptance, his sudden escape illustrates an uncommon self-awareness, a perceptive recognition that his break with the Cause must be swift and sharp or it will be no break at all. In contrast to his looping, fruitless path in Helen’s parlor, Freddy’s motorcycle trajectory is a vector: unidirectional and infinite (or so he hopes).

VI. Massachusetts

Freddie’s impulsive departure from the Cause’s ranks (or clutches) is sparked in part by his realization that Dodd will not tolerate his failures indefinitely. However, while the Cause’s dogma might contain little but psychological buzzwords and half-baked spiritual hand-waving, the personal agonies that Freddie’s Processing uncovered are not phantasmal. In particular, the regret and shame Freddie feels regarding his abandonment of Doris are still acute, still pumping poison into his heart. Paradoxically, tethering himself to the Master’s wanderings has prevented Freddie from seeking a face-to-face resolution of this painful chapter of his life. Now that he has fled the Cause, he is free to return to his native Massachusetts and visit the spawning ground of his more potent personal demons.

Freddie’s pilgrimage leads him to Doris’ childhood home, but as both A. E. Housman and Thomas Wolfe observed in their way, the dewy past and hard-edged present lie in separate hemispheres. The reunion that Freddie envisioned is not forthcoming. He only encounters Doris’ mother (Lena Ende), who with wringing hands and quavering voice explains that her daughter has long since married a local boy, moved south, and sired three children. Freddie takes this crushing news far better than one might expect, politely taking his leave while marveling that his beloved’s married name is now Doris Day. (Freddie’s return to Massachusetts is, at best, described by the title of Day’s first hit recording: “Sentimental Journey.”) Freddie could pursue Doris to Alabama and points beyond, but his New England homecoming acts like a bucket of freezing water on his need for closure. Unshackling himself from the Cause might have freed him from daily spiritual torment, but for Freddie self-improvement appears to be just as much a fool’s errand when it is pursued in solitude as with an ideological cabal.

Underlining the fact that Freddie’s ways are carved in stone, he is soon observed slipping into a drunken stupor in an otherwise unoccupied cinema while a Casper the Friendly Ghost short rolls on. This proves to be The Master’s most defiantly ambiguous scene, for after Freddie seems to fade into a deep sleep, he is awakened by an usher carrying a telephone that trails an absurdly long cord. “You have a call.” The nagging questions that might trouble a sober patron seem to slide past Freddie: Who knows that he is at the theater? How does the usher know who he is? Freddie answers the phone to find, improbably, the voice of Lancaster Dodd emerging from the handset. The Master, evincing no trace of anger towards his fugitive acolyte, asks Freddie to join him in England, where the Cause has established its own school. Dodd claims that he has, at long last, recalled the specifics under which he and Freddie first encountered one another, and that he wants to share this revelation in person. (Freddie is also tasked with restocking Dodd's supply of a favored vice, menthol cigarettes, reminding the viewer of the shared taste for pleasure-seeking transgression that once bound these two men.)

Freddie’s response is primarily one of drowsy amazement: “How did you find me?” However, Dodd’s call seems to abruptly end with the sleeper awakening again, this time to discover a theater without usher or telephone. The surrealism of the scenario points to its unreality: a message from a strangely jovial Dodd in a distant country, delivered to Freddie as though it were a cocktail on a tray. Imagined or not, Dodd’s communication provides a dose of mysticism to the film at a critical juncture in the narrative, re-establishing the well-worn Conversion Story outlines that have generally receded as Freddie’s alienation from the Cause has grown. The phone call fills the role of a divine message, a missive directly from the source of holy wisdom to the wayward lamb, conveying that all sins are forgiven and that his return will be greeted with rejoicing.

Despite the panicked character of Freddie’s flight from the Cause, his reaction to Dodd’s call seems welcoming, as though it were a message he had secretly been hoping to receive. Having fled the movement that once counted him as a brother, and then failed to discover a more personal resolution to his deep-rooted miseries, he has already begun to slide into aimless self-destruction. (Peggy’s speculation that Freddie might be “beyond help,” has begun to look fairly perceptive.) Disillusioned by the unfavorable contrast between gauzy memory and present-day reality in his old stomping grounds, Freddie allows his time with the Cause to to take on a nostalgic glint, forgetting all the anguish that he so recently fled. His frustration with Dodd (and himself) is easily set aside when he sees the prospect of re-awakening that coveted sense of belonging. Where Freddie errs is in assuming that acceptance will be as forthcoming now as it has been in the past. Unfortunately, a personal testimonial that is streaked with recidivism casts a shadow over a faith’s legitimacy, and therefore must be expunged from the evangelical imagination.

VII. England

Despite the dearth of identifying information in Dodd’s dream-call, Freddie makes his way to England and to the threshold of the Cause’s thriving new school. He strides through the door with the confidence of a long-lost scion whose return has been eagerly anticipated, but the faces that he encounters do not recognize him. Indicating a photo of Dodd on a mass-produced flyer, he lamely asserts, “I took that picture”. A faintly Orwellian odor clings to the building’s dark wood and lingers in its echoing halls: The history of the movement has already been rewritten, and it does not include Freddie. A slightly more spit-and-polish iteration of Val appears to usher Freddie into the school’s inner sanctum, where Lancaster Dodd awaits in a cavernous hall that has apparently been converted into his private office. With its towering, gothic windows of frosted glass, this magisterial chamber conveys the power and wisdom that Dodd has long craved. He is, at last, no longer an itinerant holy man, but a pontiff with his own enclave and throne.

Freddie has brought the Kools that Dodd covets, but neither the poker-faced Master nor glaring Peggy seem to be pleased to see him. Peggy in particular views Freddie’s departure from the Cause as an act of betrayal, and Dodd seems to have finally accepted his wife’s suspicions, as he is resistant to allowing Freddie to return to the movement. Indeed, Dodd exhibits no acknowledgement that the bizarre phone call to Massachusetts even occurred, leaving Freddie to wonder if he conjured the transatlantic message from his own subconsciousness.

However, one element from the call appears genuine: Dodd does in fact recall the circumstances under which he and Freddie first encountered one another. The men were friends in a past life, serving as French messengers who employed hot air balloons during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871. In the worst winter on record, Dodd explains with unconcealed wistfulness, he and Freddie lost only two balloons. Dodd may be spinning a fanciful story in order to ornament the emotional bond between the two men. However, the fondness for Freddie that he displays appears so authentic, and his longing for this dream of wartime heroics and camaraderie is so naked, it is hard to dismiss it as a mere cynical ploy.

Dodd’s reluctance to embrace his Prodigal Son a second time is rooted not in some newfound personal antipathy for Freddie, but in the danger that his habitual straying represents to the Cause. The inability to square specific failures with the general Truth of the ideology is the fundamental dilemma of the gatekeepers who peddle the evangelical imagination. In 2006, left-wing political blogger Digby turned an old Bolshevik adage on its head to draw attention to the almost Stalinist manner in which contemporary American conservatism was prepared to transform George W. Bush from a conquering saint into persona non grata:

Conservatism cannot fail, it can only be failed. (And a conservative can only fail because he is too liberal.)... In this I actually envy the right. When they fail, as everyone inevitably does at times, they don't lose their faith. Indeed, failure actually reinforces it... The Republicans are smart enough to rid themselves of failure by always being able to convince themselves that the failure had nothing to do with their belief system.

Similarly, Dodd must be rid of Freddie, or he risks a catastrophic loss of faith within his flock. The Master offers an ultimatum: Freddie may return to the fold, but only if he is willing to remain there permanently, to never again backslide or wander in search of false prophets. Reluctantly, Freddie demures, acknowledging for the first time that he cannot make such a promise: “Maybe in the next life.”

For Dodd, who views history as a continuum on which the same struggles are played out over and over, there will not be another occasion for reconciliation. He vows that when he meets Freddie again, even if if their souls are housed in different bodies, they will be sworn enemies. The wavy ritual daggers glimpsed earlier on Dodd’s desk seem permeated with potential menace, as though either man might suddenly rise and seize a weapon in order to slash the other's throat. The grand guignol bowling pin assault that caps Anderson’s There Will Be Blood hovers over the scene as well, reinforcing the ominous atmosphere and creating an expectation that Dodd and Freddie’s reunion, like that of Daniel Plainview and Eli Sunday, will end in carnage.

Dodd offers a sarcastic bit of wisdom to Freddie that succinctly summarizes the ideologue’s certainty that submission is a fact of the human condition: “If you figure out a way to live without a master, any master, be sure to let the rest of us know.” Perhaps sensing that their farewell should not occur on such an antagonistic note, Dodd suddenly breathes out a slow, mournful rendition of the pop standard “Slow Boat to China”. It is a sublimely odd flourish, one that permits the pseudo-romantic subtext of Dodd and Freddie’s relationship to be stated openly and with a level gaze. (Peggy, having departed the room in irritation, is not privy to this intimate moment.)

In the context of the master-disciple relationship, “Slow Boat” articulates Dodd’s dream of devoting himself solely to Freddie’s redemption: to get his student “all to himself alone” and “leave all the others waitin’”. Together, “out of the briny,” with all the time in the world, they might at last discover the profound transformation that has so long eluded Freddie. Dodd might be a charlatan, but in this moment, his wish seems as genuine as any romantic’s longing that life had turned out differently. For Freddie, the song not only ironically recalls his cowardly flight from Doris (aboard, as it happens, a ship bound for China), but also directly echoes his beloved’s long-ago a capella rendition of “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree,” which expresses similar, utopian dreams of exclusivity. Strange as his choice might seem at first, Dodd could hardly have selected a more affecting song with which to serenade his former apostle.

His heart unexpectedly broken, Freddie takes his leave of the Cause for the last time, and proceeds to drown his sorrows in the pints poured at a local pub. There he makes eyes at a blonde English nymph, Winn (Jennifer Neala Page), and before long the two are engaged in a sweaty, lingering, face-to-face coupling. “What’s your name?,” Freddie asks, repeating the question five times as Dodd once did during his Processing session. Here the question is posed in a moment of comparable intensity, one as sensually joyous as the Processing was brutal and cathartic. Both Freddie and Winn giggle in delight, and he declares “You are the bravest girl I have ever met.” Methods that were once implicitly sexual have becomes explicit, repurposed as a shortcut to romantic intimacy (rather than pastoral intimacy).

The temptation to regard Freddie’s "Processing-lite" pillow talk as exploitative is undercut by the ecstatic tone of the sex that he and Winn share. For the first time, Freddie seems somewhat at peace, his anger and restlessness calmed. Yet while his body might be entwined with that of a comely woman, his mind is elsewhere, as the film illustrates with its final shots. On a South Pacific beach, Freddie again lays down next to his sand-matron, nestling himself between her breast and arm, as though preparing for a long-awaited and blissful sleep.

Everything that the viewer knows of Freddie’s past behavior suggests that any reprieve from his demons will be temporary at best, and a messy demise by booze or a bloody-knuckled foe may still await him. Yet Freddie’s final exit from the Cause frees him of the torments that the ideology’s inadequacies wreaked on him. No longer will he yearn for the acceptance of a group whose anti-carnal commandments he is congenitally incapable of observing. No longer will he be deafened by the hollow clang of muddled spiritual wisdom ringing in his ears. And no longer will his failures belong to anyone else. He will be his own animal.

***

The Cause’s failures in contending with Freddie’s myriad problems—alcoholism, sexual mania, violence, impulsiveness—throw into stark relief the deep incompatibilities between his stuttering, stumbling progress towards self-improvement, and the absolutist demands of the evangelical imagination. The manner in which an ideological system confronts its own shortcomings represents a test of its flexibility and resilience. A system that permits space for intellectual modesty can limit its culpability for the fallen character of the world. The Master provides a dramatic illustration of the eruptions that inevitably occur when a system permits no limits for itself, and insists on the perfectibility of the individual and the world through the universal application of its doctrines. The presence of self-evidently imperfect believers such as Freddie denies the profound transformation that is the promise of the ideology, and thereby undercuts the missionary fervor that is needed to propel the system outward into new segments of society. Such walking imperfections cannot be tolerated indefinitely, and must eventually be either reformed by force or else expelled and denied.

A reading of The Master that foregrounds its criticisms of ideological inadequacies is, naturally, not the only analytical angle that the film permits. The sinuous, arid character of Anderson’s marvelous film allows many possible points of entry, none of them mutually exclusive: the thorny psychological terrain (and abundant twinning) in the Freddie-Dodd relationship; the problematic transition of the veteran from wartime bloodshed to peacetime domesticity; the pivotal role played by nostalgia and by what Magnolia’s Earl Partridge calls “the goddamn regret” in shaping Freddie’s actions and choices. However, one cannot neglect the role of ideology in The Master without ignoring the fundamental conflict of its narrative: the collision between the unstoppable force of an evangelical movement and the unmovable object of an unreformable soul.