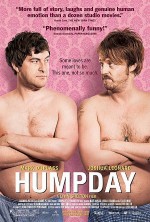

Bros on Film

2009 // USA // Lynn Shelton // July 29, 2009 // Theatrical Print

B - The aesthetic markers of the mumblecore current in independent film—handheld digital video, scruffy lighting and sound, improvised dialog, nonprofessional actors—have always seemed less essential than its scorched earth approach to the fertile comedy ground of socially awkward interpersonal situations. Mumblecore's acolytes seem to accept, as an uncontroversial given, that everything will not turn out for the best, contra Hollywood's usual comedic offerings. There's no gleefulness or operatic lustiness to this claim, as in the Coens. Rather, what emerges is a kind of woeful acquiescence to the fact that human beings will screw up everything good in their lives, usually out of narcissism. It's a bleak sentiment to be sure, but the better filmmakers can hew to this worldview while rendering the painful amusing and the amusing painful. Lynn Shelton's deliciously discomfiting Humpday, the latest offering that might reasonably be tagged with the mumblecore descriptor, is a fine example of a comedy that follows every jot of human unpleasantness while maintaining the spirited tone of an outrageous, notorious anecdote. Its Motel 6 production values are a perfect fit, but Humpday's comedy is genuine, and not dependent on indie scuzziness for its street cred.

The high concept that underlies the film would inevitably have been squandered in studio hands: two straight male friends agree to create and star in a gay porn film together. One can almost see the joyless, ugly thing that might have been born from such a story seed. Thankfully, Humpday is nothing of the sort, nor could it have been, for within its chosen stylistic parameters, anal sex wisecracks and nasty stereotypes just don't function properly. In truth, the film isn't really about homosexuality at all, except as a means examine hetero male intimacy, machismo, and anxiety. It doesn't hurt that Shelton's protagonists, Ben (Mark Duplass) and Andrew (Joshua Leonard), are a couple of liberal Seattle natives, permitting the film to dispense with the Ick Factor and dive into nastier stuff, like doubt, hypocrisy, and selfishness.

Ben and his wife Anne (Alicia Delmore) are middle-class latte-sipping types, but they gladly offer sleeping space when Ben's college buddy Andrew, a manically affable bearded vagabond, shows up at their door at 3 a.m. Twenty-four hours later, after a wild party and a bit of pot, Ben and Andrew have somehow dared themselves to have sex on camera and submit the result to the HUMP! film festival. How they got themselves into this situation—and why they just can't back down from such a ludicrous challenge—is a part of Humpday's cunning. In a sitcom, it would all be the result of a grand misunderstanding, but Shelton arrives there incrementally, by escalating the situation in small, authentic ways. Her wit is aimed squarely at the impulse among people (straight men in this context) to define themselves according to absurd criteria: sexual "victories," unfulfilled ambitions and whims, and constructed personas that are fundamentally unsatisfying.

Most of Humpday's comedy is of the cringing variety, as Ben and Andrew—generally likable fellows, but self-absorbed and simmering with indefinite angst—fumble their way through one awful conversation and confrontation after another. Duplass and Leonard in particular are fearless performers, capable of smoothing away the traces of awareness and presenting their characters are graceless Average Joes ripe for mockery. It's downright painful to watch them, but only because it's so easy to forget that one is watching a fictional feature rather than a humiliating home video. Shelton breaks up the tone of sustained social agony with cathartic quarrels and the occasional bit of slapstick, such as a scuffle over a basketball or the downright uproarious sight of Ben and Andrew's first kiss, which requires a running start. Even these elements, however, touch upon Humpday's central concerns: discontent and the fear that expression of that discontent will stray outside of acceptable boundaries.

Shelton permits her characters to wander through the uncanny events of roughly forty-eight hours at a kind of goofy, anxious amble. The pacing never really works, perhaps because there's some wheel-spinning as the film draws out the revelations, prompting the viewer to wince and long for it to end. (Is it just me, or has The Office solidified the "more-is-more" principle for squirm-worthy comedic monologues?) The absence of any epilogue, when the story practically begs for one, is also disappointing. Still, Humpday's stumbles are primarily ones of rhythm, only mildly detracting from the essential funniness of the script and performances, which possess a faux-vérité tragicomic charm. What elevates the film beyond a forgettable farce is its generous exploration of human foibles within an essentially silly situation. It's hardly a masterpiece of coal-black comedy, but it is honest and genuinely interested in scratching at everything idiotic about relationships, particularly straight male ones: the inane rituals, the selfishness, the emotional secrecy, the posturing, the defensiveness. Thankfully, Ben and Andrew are amusing in their disheveled stupidity, and Shelton's approach is never mean-spirited or snide, ensuring the film's value as both a damn funny diversion and a gentle and emotionally thoughtful tragedy.