The Spoils of Life

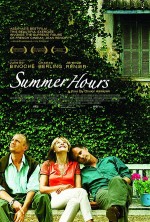

2008 // France // Olivier Assayas // June 2, 2009 // Theatrical Print

A- - The genre of family drama comes prepackaged with certain expectations regarding the rhythm and features of the narrative. The story will periodically spark and flare under the pressures of conflicting personalities, unresolved angst, and outright toxic behavior. There will be tragedies, often several of them, and secrets will emerge from musty closets. Invigorating cinema can be made from such dross—witness Jonathan Demme's Rachel Getting Married from just last year, which did Deliciously Ugly quite well. Rare, however, is the film that discovers drama within a family experience without reference to the genre's usual, ruthless patterns. Here is such a work: Olivier Assayas' delicate, dauntless Summer Hours, a marvelous film that will upend the viewer's expectations time and again. It is not the sort of cinema that offers smug familial warmth, or a free-fall of despair, or awe at the "boldness" of its directorial vision. It is, however, a work of profound beauty, with a meticulous awareness for time, spaces, objects, and emotions. It invites us to spend a year or so with an extended clan of educated, cultured people and witness their wary navigation of life, especially the parts that make the heart ache. Sound dull? Perish the thought.

The film opens on an annual summer birthday visit to the country house of Hélène (Edith Scob), a stately matriarch in a clan comprising her three adult children, their spouses, and a gaggle of grandchildren. A widow, Hélène has devoted her life to the legacy of her uncle, a modestly celebrated painter for whom she had deep affection. The house and all its furnishings are his, and since his death over three decades ago, Hélène has tended to the estate as though it were a museum. Her children, too young to cherish any memories of their great-uncle, have other concerns. Frédéric (Charles Berling) is an economist in Paris, Adrienne (Juliette Binoche) a designer in New York, and Jérémie (Jérémie Renier) an industrial manager in China. When brought together under Hélène's roof, the lines of division in their concerns and politics emerge, albeit gently. Everyone is a little self-absorbed, but no one is insufferable. They discuss their jobs, their families, their travel arrangements. They don't talk about Hélène's long months in the house with only the housekeeper, Éloïse (Isabelle Sadoyan), for company, or about how little time their mother has left.

However, Hélène wants to talk. She pulls Frédéric aside and takes him on a morbid tour of the house, cataloging the future fates of the artifacts: this desk should be donated to the museum, these sketchbooks should be sold. Frédéric doesn't want to hear it. He is put-upon and anxious about the responsibility of the estate, and uncomfortable even talking about his mother's passing. After the celebrations are over and the families hustle off, Éloïse finds Hélène sitting silently in the darkening parlor, steeping in her melancholy. Assayas then leaps forward by several months and reveals that Hélène has died. There is no trace of a shock. Death, after all, is the most expected thing in the world.

Much of Summer Hours concerns itself with the after-effects of Hélène's death, particularly the intimidating task of dealing with her uncle's furnishings, artwork, and personal effects, not to mention the country house itself. Assayas is charmingly absorbed with this process as a primary subject. Nimble as a storyteller, he leaps gracefully from scene to scene, lingering on details as necessary to evoke the simultaneously reverential and ghoulish character of the enterprise. Proximally, then, the film is a gently observed drama about how a large and valuable estate can be a stressor for the survivors. Appropriately for this purpose, there are morsels of melodrama sprinkled throughout the story, often resting wherever the differing priorities of the children intersect. Frédéric assumes that they will keep the house for communal use in the summertime, but Adrienne and Jérémie protest that this doesn't fit in with their needs or future plans. There are tensions and some harsh words, but no screaming or backstabbing. Conflicts are resolved and new hindrances crop up. The traces of Hélène are crated, rolled up, wrapped in paper, and carted away. Personal treasures are discovered and reclaimed. A discomfiting family secret emerges, but without the accompanying hideous spectacle we might expect.

If Summer Hours were solely about the tribulations of dealing with Hélène's estate, it would be a satisfying and exceptionally crafted film, albeit one that would be grasping for relevance. (Audience ambivalence is a particular hobgoblin in any film predicated on "Pretty People with Problems," as my wife would say.) As it is, Assayas uses Hélène's death as a entry point for a examination of the value of objects and places, and in particular how those values are inherently subjective, transitory, and even unstable. It's this secondary dimension of Summer Hours--emergent and yet somewhat separate from the particulars of selling artwork and dealing with attorneys--that is so captivating and stirringly conveyed. Much of the film's emotional potency derives from the talents of cinematographer Eric Gautier. Motion and framing accentuate the tone of the various spaces--a Parisian apartment, a clerk's office, a chilly museum, a cafe--without showiness, all while giving the lie to the myth of locational neutrality. (Every place has a bias and a mood, if only for a moment.) When the camera roams through Hélène's house or soars above the woodlands of the surrounding countryside, the film reaffirms with startling authority the wistfulness that undergirds the characters' nostalgia. On four occasions Assayas inventories the country house with long, wandering sequences, noting its transformation from shrine to shop to shell to--wittily, unexpectedly--a liberated space for boisterous adolescents. In recent years Gautier brought sensory sizzle to Into the Wild and Private Fears in Public Places, two films that fall firmly under the umbrella of Ambitious, Annoying, and Beautiful to Look At. This film represents a far greater achievement, as Assayas utilizes Gautier's camera to decisively and poignantly convey theme.

Summer Hours is a film highly attuned to the subtle, often contradictory currents tugging at the characters. Rather than spurring them into a collision just to see the catastrophic consequences, Assayas permits the family members to wrestle with challenges as humans would in real life, their agony evolving and their frustration palpable. Sometimes the characters convert others to their way of thinking, sometimes they suffer in silence, and sometimes they are diverted by other tasks. Another film, a less innovative and touching film, would find ample opportunities for shrill and distracting melodrama: Frédéric's daughter's arrest for shoplifting, Éloïse's unfortunate preference for a particular vase, Adrienne's sudden confession of her engagement. Any one of these plot threads might have led to a narrative explosion with consequences rippling far and wide. Assayas offers something far more sophisticated. His explosion is a whimper, a death that is neither exceptional nor unexpected, but he traces its ripples with impressive sensitivity for sorrow's mutability, as well as respect for the highly personalized way that people view objects and places.