You Like This

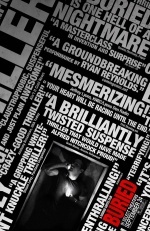

2010 // USA // David Fincher // October 4, 2010 // Theatrical Print (St. Louis Cinemas Moolah Theater)

B+ - The tumultuous story of the founding of the social networking site Facebook is the sort of tale that seems ripe for grandiose declarations about How Everything Is Different Now. Leave it to David Fincher to find a much more fascinating approach, one that acknowledges the revolutionary nature of Web 2.0 while maintaining a plaintive distance (and without striking the pose of a Luddite killjoy). Curiously simple in its broad outlines, but gratifyingly intricate in the particulars of its construction, The Social Network is partly a hoary tragedy of betrayal, and partly a jittery, uncertain assessment of where we find ourselves, culturally speaking, in the twenty-first century. Much like the two works that established the director as an invigorating visual storyteller—Se7en and Fight Club—the new film is firmly grounded within Fincherverse, a (slightly) Bizarro cousin of our contemporary world, awash in the greasy shadows of dissipation and despair. Never mind that The Social Network's environs roam from the burnished walnut and brass of the Harvard campus to the frosted glass and Aeron Chairs of Palo Alto. Fincherverse is conspicuously fast, cheap, and out-of-control, to borrow a phrase. Here, underneath the slick metal casing of a multi-billion-dollar rocket ship of an idea, one finds a toxic cocktail of crass misogyny, petty resentments, class jealously, and jaw-dropping arrogance. And damn if it isn't entertaining to watch that witch's brew roil.

At Harvard in 2003, undergrad computer science whiz kid Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg, magnificently cast), having just been abruptly (and perhaps wisely) dumped by his girlfriend, proceeds to drunkenly slander her on his blog. He then stays up all night coding a crude "Who's Hotter" site that pulls photos off the "facebooks" of the university's houses and clubs, with help from his programmer roommates and his best friend, economics prodigy Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield). The glut of Internet traffic Zuckerberg's trifle generates catches the attention of both the campus IT staff and Harvard's more elite student circles. In the latter category are identical twin rowing stars Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss (Armie Hammer, portraying both brothers) and Divya Narendra (Max Minghella), who offer Zuckerberg a job programming a new college social site called ConnectU. Before you can say "handshake agreement," Zuckerberg has launched his own social site, The Facebook, with seed money from Saverin, all the while running interference against the Winklevosses. The Facebook explodes on the Harvard campus, turning both Zuckerberg and Saverin into small-pond nerd rock stars (complete with groupies), and sending the Winklevosses into gentlemanly fits of apoplectic rage. Dispel any illusions, however, that this is a fist-pumping real-world Revenge of the Nerds story.

Zuckerbeg sets his sights on expanding The Facebook to other campuses while insisting on the necessity of preserving its hip image, even as Saverin frets about the necessity of bringing in advertising dollars. Saverin's fate is sealed, however, with the appearance of Napster creator Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake). Charming, enthusiastic, and slick as owl shit, Parker tells Zuckerberg everything he wants to hear and seduces the undergrad to move Facebook's base of operations to Silicon Valley. Suffice to say that the rest of the tale if full of acrimony and treachery, not so much because the narrative trajectory of The Social Network strongly signals it (although it does), but because the bulk of the story is told in flashback, as Zuckerberg gives deposition in two multi-million dollar lawsuits: one launched by the Winklevosses and one by Saverin himself. This "Tell Us What Happened" structure gives Fincher and editors Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall the space to deliver some of the most exhilarating cross-cut storytelling in the director's oeuvre, surpassing even that of Fight Club and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. To be sure, it's an approach that's chock full of landmines and occasions for uninspired laziness. Exhibit A: In the deposition scenes, a lawyer will ask, "And what did he say?," followed by a cut that reveals what was said. Yet Fincher not only makes such exchanges dramatic, he makes them cinematic. The persuasive performances, the chiaroscuro photography by Fight Club alum Jeff Cronenweth, and the score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Rose all cohere to establish the film's curious aura of electric expectation veined with defeated desolation.

The mode that Fincher has adopted keeps the viewer conscious of the looming fiscal and personal eruptions (whether one knows the Facebook story or not), and of the intrinsic unreliability of the perhaps self-serving recollections that comprise most of the film's action. This is Greek tragedy, sans the cosmic meddling and with a double shot of human hubris, although here the tale ends not in collapse but with billions in assets and nagging questions about what has been (and is being) accomplished. Despite its thrills (and laughs), The Social Network is not an easy film to cozy up to. It is a story that simmers with mistrust, almost to the point of thematic fixation. The Winklevosses and Saverin fail to appreciate Zuckerberg's cold ambition. Saverin is crippled by odd suspicions, but doesn't see the locomotive of perfidy speeding towards him. Zuckerberg constantly parses others' words for slights, even as his vanity and callousness alienate everyone around him. Friendships and relationships erode and then give way like muddy riverbanks, while others explode suddenly in a combustible cloud of duplicity (real and imagined). Zuckerberg asserts that he wants to replicate the social experience of college online, but Facebook's genesis seems to throw everyone involved into a scumpool of high school nastiness. There's nothing smugly celebratory about Fincher's cynical conception of human nature, just resignation and bemusement, coupled with cool uneasiness about how such stories will play out in a future of digital pseudo-connectedness.

The screenplay by Aaron Sorkin overflows with the writer's trademarked high-velocity, fussy dialog, but it's fitting to hear it on the lips of Harvard undergrads and Internet moguls, whose minds seem to be whirring at supersonic speeds. In fact, a few ridiculously on-the-nose lines aside, The Social Network proves to be Sorkin's deftest script since his mostly forgotten Hitchcock homage, Malice. The film's casting is uniformly superb (and even a little sardonic in the case of Timberlake as the man who throttled the life from the recording industry), although the performances themselves mostly range from the smoothly functional to the warmly welcome. The exception is Eisenberg, who gives the best performance of his career, easily surpassing any of his recent comedic roles and even topping his breakout turn in The Squid and the Whale. The "Michael Cera's understudy" cracks—which yours truly has been guilty of voicing—should be put away now. Eisenberg conveys Zuckerberg's essential blend of aspiration, bitterness, social gracelessness, and self-aware brilliance with spooky precision. However, there remains something inscrutable in the portrayal, and it is this elusive glimmer of unsettling genius—the sense that he's thinking three steps ahead of us mere mortals—that makes Eisenberg's performance such a feat. Although The Social Network is decisively an ensemble film, Eisenberg's dominance underscores the centrality of Zuckerberg's intellect and ego to the tale of Facebook. While Fincher glibly and not-so-subtly suggests that the man's drive is rooted in his need to impress the Girl That Got Away, such (fictional) psychological speculation is less compelling than the film's broader (but no less glib) narrative of Nixonian resentment. If Zuckerberg the character has an arc at all, it is one characterized primarily by a sudden revelation: exclusivity is no longer a desirable feature. Without a prayer of getting into Harvard's elite social clubs, Zuckerberg founded his own club, made himself president, and (eventually) let the whole world in the door. Now you'll have to excuse me; I need to post this review on Facebook.